[For English readers, please scroll down to find the English version of this interview]

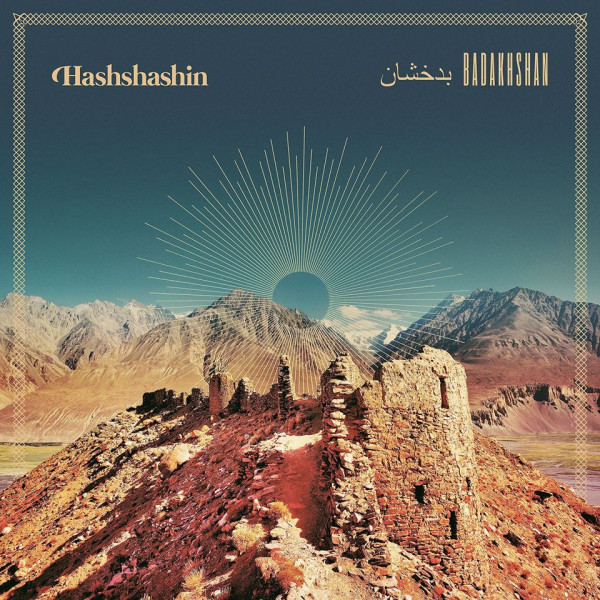

Nous vous avons récemment parlé d'Hashshashin, trio australien à la croisée du post-rock, du metal progressif et de la musique traditionnelle du Moyen-Orient. Nous avons voulu en savoir un peu plus sur cette formation qui a su nous faire voyager à travers son second album, Badakhsan. C'est pourquoi nous avons profité de cette période de confinement pour poser quelques questions à Lachlan R. Dale, leader de la formation et également patron du label Art As Catharsis.

Bonjour Lachlan et merci d’avoir accepté cet entretien pour La Grosse Radio. Comment vas-tu, et comment va le groupe, en cette période de quarantaine ?

Nous avons été plutôt chanceux. Nous pouvons toujours travailler malgré la situation, et cette dernière est globalement stable ici en Australie. J’en profite pour écrire et enregistrer de nouvelles compositions, et pour poursuivre mon apprentissage de la musique traditionnelle afghane avec le rubab.

J’aimerais que l’on évoque Badakhshan, votre dernier album, sorti à l’automne 2019. Ce nom correspond à celui d’une province située à la frontière entre l’actuel Tadjikistan et l’Afghanistan. J’imagine qu’il est inspiré de l’un de tes voyages. Peux-tu nous en dire plus ?

En 2017, j’ai passé un mois en Asie centrale, à voyager dans les montagnes du Pamir avec ma compagne et quelques amis. C’est une région incroyable, marquée par des paysages désolés, de magnifiques vallées luxuriantes parsemées de yacks et de tentes nomades, et des avant-postes soviétiques abandonnés. J’en ai gardé quelques souvenirs marquants : cheminer dans les montagnes depuis la cité d’Osh, au Kirghizistan, et traverser les basses terres verdoyantes peuplées de milliers de chevaux. Passer une journée au Horse and Yak Festival, sous l’immense et glacé pic Lénine, où les nomades jouaient une forme de polo brutal et chaotique, avec une chèvre sans tête en guise de balle. Le paysage surréaliste d’Alichur, une ville en brique crue située en haute-altitude, près d’un lac bleu incandescent (cette région est baignée d’une lumière incroyable). Descendre l’autre versant du Pamir et voir les montagnes déboucher dans le corridor de Wakhan, la frontière avec l’Afghanistan, encadrée par les montagnes de l’Hindu Kush. Mon dieu, qu’est-ce que je fais à la maison ?

Un jour, nous sommes tombés sur un abri radar désaffecté dans le Haut Pamir, qui produisait un grand et bel écho. J’ai attrapé mon komuz (un instrument kirghize) et j’ai commencé à jouer. Conor Ashleigh, un ami réalisateur, a filmé. Il a ensuite fait un montage avec des scènes de notre voyage, et a sorti un film magnifique que nous avons appelé Aftaab e Badakhshan (Le Soleil du Badakhchan). Ce film est sûrement l’une des plus belles façons de saisir la beauté de cette région.

Ta musique est un mélange entre post-rock instrumental, metal progressif et musique traditionnelle orientale. Comment définirais-tu votre style musical ?

J’ai toujours eu du mal à répondre à cette question, car ma réponse change considérablement selon l’expérience musicale des gens. Je commence généralement par quelque chose de vague et d’opaque, comme “musique psychédélique moyen-orientale et drone” puis j’étoffe en fonction du degré d’intérêt ou d’incompréhension. Si l’on insiste, je dirais que nous combinons des éléments du rock et du metal progressif, de la musique psychédélique, du drone, et du post-rock avec des influences issues de l’Afghanistan, du Tadjikistan ou de l’Iran, même si je dois avouer que j’ai encore l’impression d’aborder superficiellement ces cultures. Nous avons toujours été tous les trois attirés par les mesures asymétriques et la polyrhythmie, associées au contre-temps. La combinaison de ces éléments et de mon amour pour le drone forme le cœur de notre musique.

Vous êtes un groupe australien qui inclue des influences moyen-orientales, éloignées de votre pays. Pourquoi avoir fait ce choix et que représentent ces influences pour vous ?

Encore une question difficile ! J’y pensais justement l’autre jour : d’où me vient cet intérêt pour la musique orientale ? J’ai une très mauvaise mémoire : la plupart de mes souvenirs s’estompent. Il y a pas mal d’années, je me souviens avoir été intéressé par la “musique du Moyen-Orient”, mais sans avoir creusé plus que ça. La musique de Secret Chiefs 3 a vraiment été une influence majeure quand j’étais plus jeune, mais c’est véritablement ce voyage dans le Pamir qui m’a donné l’impulsion pour m’y plonger pleinement. Aujourd’hui, je peux dire avec certitude que la musique classique nord-indienne, afghane et iranienne est la base de ma culture musicale. Concernant la signification de cette musique, je dirais qu’elle est marquée en terme de style et de technique par de beaux mouvements fluides et complexes, à l’image des solistes classiques occidentaux, qui jouent constamment avec les temps, en créant des subdivisions, en superposant des rythmes, en jouant des séquences de longueur et de mètres différents, en ralentissant et en accélérant.

Mais je pense qu’il y a quelque chose de plus profond. J’ai toujours été dégoûté par l’influence du capitalisme consumériste et du néolibéralisme dans l’industrie musicale occidentale. On s’est habitué à voir la musique comme un “produit”, dont l’identité et la marque sont au cœur de l’ensemble. Nous oublions qu’il y a d’autres façons de considérer la musique : comme un rituel, un rite, un moyen d’induire un certain état de conscience ou une expérience, une façon de lier des groupes, une offrande, de la magie, etc. Nous sommes piégés dans une vision très restreinte et peu inspirée de ce que la musique devrait ou pourrait être.

J’ai ce besoin d’exprimer quelque chose à travers la musique, un besoin que je ne peux pas traduire en mots. Je l’ai expliqué précédemment en soulignant que l’Occident avait considérablement perdu les outils lui permettant d’induire une expérience mystique : mais je pense que cela va bien au-delà. Nous avons perdu une façon particulière de voir le monde. Nous pourrions l’appeler le « monde enchanté », ce qui semblerait assez étrange. Nous avons réduit le monde et toute son immanence rayonnante au statut d’objets morts, inertes, séparés. Nous ne voyons pas son unité, sa contingence et son interdépendance (et je tiens à mentionner ici mon rejet de la spiritualité New Age). Nous avons oublié que nous faisons partie du monde, que nous n’en sommes pas séparés : je pense vraiment que cela est dû au prisme corrompu, malade et incroyablement limité du néolibéralisme, du capitalisme de consommation, et d’un type particulier de rationalisme scientifique qui exclut une majorité du monde afin de pouvoir l’appréhender.

Le terme Hashshashin fait référence aux assassins islamistes du XIIIe siècle. Peux-tu nous expliquer votre choix ?

Tout d’abord, j’aimerais dire que nous sommes conscients de tous les mythes idiots et racistes concernant les Hashshashin, et que nous les rejetons. Mais nous reconnaissons également que nous sommes des étrangers, qui nous plongeons dans des cultures orientales : nous avons donc choisi ce nom en toute conscience, afin de souligner notre origine allochtone, et le fait que, même si l’on fait tout notre possible, nous ne parviendrons pas à saisir la nature véritable des traditions musicales dans lesquelles nous nous sommes engagés. Familièrement parlant, « Hashshashin » peut également signifier « racaille bruyante » ou être utilisé en argot pour désigner un consommateur de drogues. Les deux significations sont assez pertinentes.

Tu joues beaucoup d’instruments sur cet album, comme le rabab afghan, le bouzouki irlandais et le setar perse. Peux-tu nous les présenter ?

Le rubab afghan est l’instrument national de l’Afghanistan. Il était utilisé à la cour, et a été influencé par les échanges culturels entre le Nord de l’Inde et l’Afghanistan (d’où les cordes sympathiques, qui, à l’instar du sitar, créent de magnifiques harmonies et sustains). Ustad Mohammad Omar, Ustad Rahim Khushnaqaz, Qais Essar et Homayoun Sakhi font partie de mes joueurs de rubab préférés.

Le setar perse est un instrument de base de la musique classique persienne et iranienne. Je suis moins familiarisé avec son histoire, mais je vous recommande fortement les musiciens classiques perses Ustad Mohammad Reza Lotfi, Ali Ghamsari et Kayhan Kalhor. Malgré mes recherches poussées effectuées avant mon voyage au Tadjikistan, je ne connaissais pas l’existence du setar. J’ai vu Ustad Shavkmamad Pudlov se produire avec un ensemble au festival Roof Of The World à Khorog et j’ai été scotché. Le setar semble vaguement lié au dutar et au tambour (qui existent sous des formes variées en Asie centrale et orientale) ainsi qu’au sitar indien.

Les morceaux de Badakhsan sont plutôt longs et progressifs (entre 8 et 12 minutes pour la plupart d’entre eux). Est-ce important pour toi de créer un format long afin de laisser s’installer une ambiance ?

Sur cet album, nous avons tenté d’expérimenter des répétitions et de créer en fonction de l’état d’esprit : s’assoir simplement avec un riff ou une idée, et laisser les choses se faire naturellement. Nous avons été inspirés par des groupes comme The Necks, Tangents et Dawn of Midi, qui ont de belles et subtiles progressions dans leur musique, bien que je pense que nous sommes loin d’y parvenir. Dans la musique orientale traditionnelle et rituelle, la répétition de certains motifs devient comme un mantra permettant d’induire un état de transe, et une connexion avec Dieu. C’est une idée ou une pratique qui m’intéresse, alors on s’y est attardé sur cet album. J’ai d'ailleurs l’impression que, ces derniers temps, je me concentre de plus en plus sur cette idée dans mes performances solo, avec des boucles simples et des motifs drones couplés à de l’improvisation. Et oui, nous aimons tous la musique progressive. Nous avons expérimenté plusieurs façons d’écrire sur cet album. Et nous avions de besoin d’un certain temps pour clore les idées que sous-tend chaque morceau.

Bien que votre musique soit instrumentale, beaucoup d’images viennent à l’esprit, évoquant ces paysages. Vous avez réalisé un clip pour « Crossing the Panj » qui est plutôt psychédélique. Avez-vous pensé à réaliser un clip incluant des paysages du Badakhchan ?

Oui, mais je l’ai déjà fait avec Conor Asleigh pour Aftaab e Badakhsan. Mais cela aurait bien marché. J’ai notamment écris « Death in Langar » assis dans un appartement à Almaty après notre voyage, avec le setar Pamir que j’ai récupéré à Khorog. La musique évoque ces paysages.

Comment décides-tu des titres des morceaux ? Puisque qu’il s’agit d’une musique instrumentale, écris-tu le titre après avoir composé le morceau, en fonction de ce qu’il évoque ? Ou bien pars-tu du titre pour composer ?

Nous avons défini les titres et créé un concept cohérent après avoir écrit l’album. J’ai l’impression qu’une grande partie du processus de composition est inconscient, comme si j’essayais de saisir des idées à moitié formées dans mon subconscient, ou que je cherchais quelque chose que je ne suis même pas capable de définir. Quand je compose un morceau, j’essaie d’y mettre certaines émotions ou certaines expériences, il est donc logique d’y retrouver des idées clés et des choses vécues.

Il faut que je précise également que je ne suis qu’un tiers du groupe. Notre batteur, Evan, a une façon totalement différente et fascinante d’écrire, de composer et d’enregistrer des morceaux, influencée par les différentes manières d’aborder la musique selon les cultures. Il a un incroyable cerveau mathématique, ou du moins rythmique. La façon dont il créé ces merveilleuses mesures asymétriques me dépasse. Vous pouvez entendre sa manière très logique de composer dans son groupe HELU, et même dans son groupe précédent Squat Club, que j’adore tous les deux. De même, notre bassiste Cam a une approche totalement différente. J’espère qu’il ne m’en voudra pas de le définir ainsi, mais c’est un musicien instinctif et incroyablement intuitif : il n’a pas besoin de conceptualiser les choses de façon complexe, parce qu’il est totalement présent et connecté à ce qu’il joue. Il n’y a pas de distinction entre son jeu et lui-même : il est totalement immergé dans la musique, là où j’aurais tendance à me perdre dans toutes ces abstractions ridicules. Il est d’ailleurs plutôt efficace pour nous ramener à la réalité, Evan et moi, quand nous partons dans de longues digressions. Cam a une façon incroyable de se connecter et de ressentir la musique, ce qui n’exclut pas qu’il soit très technique : Evan et lui sont bien plus techniques que je ne le suis. Son travail superbe avec Five Star Prison Cell en témoigne. Qu’obtenez-vous donc en mélangeant tout ça ? Trois ans de réflexion sans fin, d’essais, d’expérimentations, d’enthousiasme, de désillusions, et puis, finalement, Badakhshan. C’était un album difficile à finaliser, mais nous avons réussi, et j’en suis très fier.

Badakhshan fait suite un à premier album sorti en 2016, Nihsahshsah. Les deux albums ont-ils été composés de manière très différente ?

Oui, tout à fait. Pour la plupart des morceaux de Nihsahshsah, j’ai apporté au groupe une série de riffs ou de structures quasi-complètes. Cela n’a pas posé de soucis je suppose, mais c’était assez limitant. Evan et Cam ont développé avec brio des idées et des contre-points autour de ces structures, ce qui est génial car sans cela je pense que l’album aurait été assez ennuyeux. Mais j’ai eu la sensation d’être trop dirigiste. Cette approche n’utilisait pas assez les talents et capacités du reste du groupe.

Nous avons testé beaucoup d’approches différentes (pour le second album, ndlr), généralement via l’improvisation. J’apportais toujours des structures quasi-complètes au groupe, mais cela ne nous dérangeait pas de les déconstruire et de les reconstruire. Ainsi, je peux apporter un morceau entier et les gars peuvent me convaincre de tout jeter à l’exception d’un unique riff au milieu, qui deviendra notre point de départ. Evan a été obsédé pendant un temps par des « rythme parfaitement formés » selon la géométrie euclidienne (ne me demandez pas ce que ça veut dire). C’est ainsi que "The Shrines of Wakhan" a été conçu, en improvisant sur la base des rythmes créés par Evans.

Cet album (Badakhshan, ndlr) a été beaucoup plus collaboratif. A titre personnel, je voulais élargir la gamme de sons et de styles que j’utilisais. J’ai essayé d’apporter tous ces nouveaux instruments, ce qui a nécessité dans un premier temps que j’apprenne à en jouer correctement, puis que je surmonte les défis techniques un peu délicats pour pouvoir les amplifier. Il y a eu un moment assez court où nous sommes passés d’une salle de répétition entièrement amplifiée à la chambre de Cam, chez lui, et où nous avons tenté de sonner comme un groupe acoustique. Tout cela était passionnant, mais également très déroutant et frustrant. Cet album nous a demandé beaucoup de travail.

Tu possèdes également deux labels, Art As Catharsis et Worlds Within Worlds, dont le nom évoque la musique que tu joues avec Hashshashin. Comment choisis-tu les artistes avec lesquels tu signes ?

Très bonne question. Art As Catharsis se concentre plus sur une musique avant-gardiste, progressive et cathartique issue du mileu underground australien. Bien que les styles soient très variés, on y trouve des sujets et des idées communs qui permettent de construire notre catalogue, qui a environ 130 sorties à ce jour. Worlds Within Worlds est mon label le plus récent, portant sur la musique intrumentale orientale, à la fois classique et contemporaine. Les deux labels sont dérivés de ma propre envie d’explorer de nouveaux sons et de nouvelles idées, ainsi que de ma volonté d’utiliser mes compétences afin d’aider des artistes à toucher un public plus large.

Je suppose qu’avec le coronavirus, vous ne pouvez plus partir en tournée. Comment vois-tu le futur du groupe avec cette crise ? Composes-tu pendant cette période de quarantaine ?

Nous ne sommes pas un groupe habitué aux grosses tournées. On a vraiment de la chance si l’on fait un concert par mois, et c’est par choix. Nous avons cependant vécu des concerts supers, notamment lorsque j’ai monté une tournée avec le musicien afghan-américain Qais Essar. En tant que groupe, nous ne nous mettons pas la pression. Nous jouons quand nous le souhaitons, et nous composons quand nous en avons envie. Nous n’avons pas besoin de brusquer les choses. Mais je pense que cela nous manque à tous de ne pas pouvoir nous retrouver (nous sommes des amis proches) et de composer en groupe. J’ai un tas de compositions au rubab que j’aimerai jouer aux gars pour voir ce qu’ils en pensent. Mais pour l’instant, je me concentre en particulier sur mon premier album avec Black Aleph, sur mes compositions solos (j’aurai bientôt un morceau complet qui va sortir) et sur un projet collaboratif que je fais avec un groupe de musiciens orientaux. Comme je l’ai déjà dit, j’essaie également de m’améliorer au rubab. C’est un instrument difficile, et j’ai pas mal de chemin à faire jusqu’à sa maîtrise.

Nous vous souhaitons le meilleur, et te laissons conclure cette interview. As-tu un dernier mot pour nos lecteurs ?

Merci sincèrement pour votre intérêt, cela compte beaucoup pour nous.

Interview réalisée par mail en avril 2020

Merci à Céline pour la traduction

Photographies : © Rhiannon Hopley

[ENGLISH VERSION]

Hi Lachlan and thank you for allowing us to do this interview for La Grosse Radio. First of all, how are you and the band during this global quarantine period ?

We’ve all been pretty fortunate. We’re all still able to work under these conditions, and things are generally pretty under control here in Australia. I’ve been using my time to write and record new music, and to continue to learn classical Afghan music on the rubab.

I would like to talk a bit about Badakhshan, your last record, released during the autumn 2019. The name derives from a region located at the border of the actual Tadjikistan and Afghanistan. I assume you've made a journey there to find the inspiration. Can you tell us what you've found ?

In 2017 I spent a month in Central Asia, travelling through the Pamir Mountains with my partner and a few friends. It is an incredible region, marked by desolate landscapes, beautiful, lush valleys spotted with yaks and nomad tents, and decaying Soviet outposts. There are a few memories that really stand out: making our way into the mountains from the city of Osh in Kyrgyzstan, and passing through the green lowlands populated with thousands of horses. Spending a day at the Horse & Yak Festival under the immense, ice capped Peak Lenin, where nomadic people played a brutal and chaotic version of polo with a headless goat as the ball. The surreal landscape of Alichur, a high altitude mud-brick town set beside an incandescent blue lake (that region is flushed with the most incredible light). Coming down the other side of the Pamirs and seeing the mountains fall away to the Wakhan Corridor – the border of Afghanistan framed by the towering Hindu Kush Mountains. My god, what am I doing sitting here at home?

One day we came across an abandoned radar shelter in the High Pamirs, which had beautiful, long reverb. I grabbed my komuz – a Kyrgyz instrument – and started playing inside. Conor Ashleigh, a friend and film maker, captured it. He combined that footage with scenes from across our trip, and created a beautiful film we called Aftaab e Badakhshan, or, The Sun of Badakhshan. That film is probably your best bet to get a sense of the region.

Your music is a mix between instrumental post-rock, progressive metal and Middle East influences from that region we mentioned earlier. How would you define your musical style ?

I always struggle with this question, because the answer really changes depending on the individual’s experience with music. I usually start with something vague and opaque, like “Middle Eastern psychedelia and drone”, and then elaborate based on the level of confusion or interest. If I’m pushed, I would say that we combine elements of progressive rock and metal, psychedelia, drone and post-rock with influences from Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Iran - though I have to admit I still feel we are in the very early stages of engaging meaningfully with those cultures. All three of us have always been drawn to polyrhythms and polymetrics – rhythms juxtaposed and oscillating around a counter-rhythm. That, combined with my love of drone, really forms our core sound.

You are a band from Australia, including Middle East influences, a region far from where you live. Why did you do that choice and what does this Middle East music represent for you and the band?

Another difficult question! I was thinking about this the other day: where did my interest in music from the East come from? My memory is pretty awful: most things rapidly fade into mist. I can remember having a sense for many years that I was interested in “music from the Middle East” but never really followed through on that sense. The music of Secret Chiefs 3 was definitely a formative influence when I was younger, but this trip to the Pamirs gave me the momentum I needed to really delve deep. These days I can more confidently say that the classical music of North India, Afghanistan and Iran makes up the bulk of my musical diet. As for what the music represents: well, in terms of style and technique, it's marked by very complex, beautiful, fluid movements - in a similar way to Western classical solo musicians, who are constantly pushing and pulling time, creating subdivisions, overlaying rhythms, playing sequences of different length and metres, slowing down and speeding up. In these styles there is often a focus of a drone note throughout, which aligns with my long time fascination with drone.

But I think there is also something deeper at play. I’ve always had a distaste for the influence of consumer capitalism and neoliberalism on the music industry in the West. We are trained to see music as a ‘product’, and identity and branding as a core part of the package. We forget that there are other ways to regard music – as ritual, as rite, as a way to induce a certain state or experience, as a way to bind groups, as an offering, as magic (etc). We have trapped ourselves in a very limiting and rather uninspiring vision of what music can or should be.

I have this impulse to want to try and express something through music that I can’t put into words. I’ve previously articulated this by pointing out that the West has largely lost the tools by which to induce mystical experience – but I think this points to something broader. We’ve lost a particular way of seeing the world. We could call it the ‘enchanted world’, which sounds pretty strange. We’ve reduced the world and all of its radiant immanence to the status of dead, inert, separate objects. We fail to see its unity, contingency and interdependence (and I do want to be careful to mention my rejection of New Age spirituality here). We’ve forgotten that we are of the world – we are not separate to it – which, really, I could tie back to the corrupting, diseased and incredibly limited lens of neoliberalism, consumer capitalism, and a particular type of scientific rationalism that is forced to banish the majority of the world in order to grasp it.

Hashshashin derives from assassins in Islam back in the 13th century. Can you develop the idea behind this band name ?

Well, first I need to point out all the stupid and racist myths about the Hashshashin. We are aware of those images, and we reject them. But we also recognize that we are outsiders, who are engaging with a range of Eastern cultures – so we chose that name with an element of self-awareness: it communicates our separateness, and the fact that, no matter how hard we might try, we are always going to misperceive and project onto the traditions we are engaging with. Colloquially, Hashshashin can mean ‘a noisy rabble’, or be used as slang to indicate a drug user. Both those uses are pretty relevant.

You play a lot of instruments on this record, like Afghan rabab, Irish bouzouki and Persian setar. Can you introduce them to us ?

The Afghan rubab is the national instrument of Afghanistan. It was used in court music of Afghanistan, and has been influenced by cultural exchange between north India and Afghanistan - hence the sympathetic strings which, like a sitar, create beautiful overtones and reverb. Some of my favourite players include Ustad Mohammad Omar, Ustad Rahim Khushnaqaz, Qais Essar and Homayoun Sakhi.

The Persian setar is a staple of the classical music of Persia/Iran. I’m less familiar with its history, but can highly recommend Ustad Mohammad Reza Lotfi, Ali Ghamsari, and Kayhan Kalhor as some of my favourite Persian classical musicians. Despite research heavily before my trip to Tajikistan, I was unaware of the existence of the Pamiri Setor until I encountered it in person. I saw Ustad Shavkmamad Pudlov perform with an ensemble at the Roof Of The World Festival in Khorog and was hooked. At least superficially it seems related to dutar and tambour (which exist in various forms across the East and Central Asia) and even the Indian sitar.

The songs on Badakhstan are mostly pogressive and long ones (mostly between 8 and 12 mn). Is it important for you to let the ambiance takes its place with this format ?

On this record we tried to experiment more with repetition and mood: to just sit with a particular riff or idea for some time and let it naturally develop. We took some influence from bands like The Necks, Tangents and Dawn Of Midi, who have the most beautiful, subtle progressions in their music (though I think we are a far cry from achieving anything like that). In some Eastern classical and ritual music, the repetition of particular figures becomes something like a mantra that helps induce a trance-like state, and connection with God. That’s an idea or a practice that I’m quite interested in, so we touched on that with this album. (These days I feel like I’m focusing more and more on this idea in my solo performance, looping simple, droning figures and improvised over the top.) And yes, we all love progressive music. We experimented with different approaches to songwriting on this album. It seemed like we just needed a reasonable amount of time before we concluded the ideas underpinning each song.

Even if your music is instrumental, there are many images that come in mind, evocating those landscapes. You've made a video clip for "Crossing the Panj", using psychedelic images. Did you consider to make a video clip including pictures of Badakhshan landscapes ?

Yes, but I’d already done that with Conor Ashleigh for Aftaab e Badakhshan. It certainly would have fitted well. For instance, I actually wrote "Death In Langar" sitting in an apartment in Almaty after our trip, with the Pamiri Setor I picked up in Khorog. The music is evocative of that landscape.

How do you decide of the songs titles ? Because the music is instrumental, do you write a title after composing the music, considering what the music evokes to you ? Or do you put those words on a white page and try to develop musically those thematics?

We attached the song titles and the unifying concept after we’d written the record. I feel like so much of the process of making music is not accessible to consciousness – like I’m grasping at half formed ideas in my sub-conscious, or looking for something that I’m unable to even define. When I write music, I try and channel specific emotions and experiences into whatever I’m playing, so it makes sense that key ideas and experiences make their way into our music. At this point I think I just need to say that I’m still just one third of the band. Our drummer, Evan, has a very different, and absolutely fascinating take on writing, composing and performing music – also informed by the different perspectives that other cultures take on the role of music. He has an incredible mathematical brain, or a least rhythmic brain. How he creates these wonderful polymetrics is far beyond me. You can hear the logical development of his approach to music in his band HELU, or even in an earlier band Squat Club – both of which I adore. Then we have our bassist Cam, who again has a radically different tact. I hope he doesn’t mind how I characterize this, but he is an incredibly intuitive and instinctual player: he doesn’t need complex conceptualizations, because he is fully present and connected with playing. It's like there is no space between his performance and his self: he is fully embodied, whereas I tend to get lost in all of these ridiculous abstractions. To that end, he is usually pretty helpful in bringing Evan and I back to reality when we go on long, tangential discussions.

Cam has an amazing ability to connect-with and feel music, which is not to say he isn’t an excellent technical player – because both he and Evan are far more technically accomplished than I am. His wonderful work in Five Star Prison Cell is a testament to this. So mix all that together and what do you get? Three years of endless theorizing, playing, experimentation, excitement, disillusionment – and then finally, Badakhshan. This was a tough record to finish, but we did it, and I am very proud.

Badakhshan follows a first record you've made back in 2016, Nihsahshsah. Did the composition process differ on both records ? How did you create this music ?

Yes, absolutely. For most of Nihsahshsah, I would bring a series of riffs and a near-completed song structure to the band for us to develop. That was fine, I guess, but it also felt quite limiting. Evan and Cam did amazingly to develop ideas and counter-points around my skeleton - which is great, because without that I think the album would be boring as hell. But I felt like I was being too prescriptive. That approach really didn’t utilize the great skills and talents of the rest of the band. We experimented with a lot of different approaches, generally through a lot of free improvisation. I still brought a few near-completed structures to the band, but we were very happy to tear them apart and rebuild them. Say, I might bring a full song and the guys might convince me to throw away everything apart from a single riff in the middle, which would become our starting point. For a while Evan was obsessing over ‘perfectly formed rhythms’ informed by Euclidean geometry (don’t ask me what any of that means). And so, "The Shrines Of Wakhan" started with the three of us improvising over one of the rhythms Evan had created.

This one was a lot more collaborative. Personally, I wanted to expand the range of sounds and styles I was offering. I tried to bring in all these new instruments – which first necessitated me getting relatively comfortable with each of them, and then overcoming the quite daunting technical challenges of amplifying them. There was actually a short period where we moved from a fully amplified rehearsal room to a bedroom in Cam’s house, and where we experimented with becoming an acoustic band. All of this was exciting, but also highly confusing and frustrating. This record took a lot of work.

You also own two record labels, Art as Catharsis and Worlds Within Worlds. Those label names are very evocating of the music you play with Hashshashin. How do you choose the music you want to promote on your record companies ?

Great question. Art As Catharsis focuses on forward-thinking, progressive and cathartic music from the Australian underground. While the range of styles is very broad, I think there are themes and ideas that help underpin our catalog, which is sitting at around 130 releases at this point. Worlds Within Worlds is my newer label, which focuses on classical and contemporary instrumental music from the East. Both labels are an extension of my own exploration for new ideas and new sounds, and my passion for using my skills for helping artists reach new audiences.

I assume that with the Coronavirus you cannot play or tour anymore. How do you see the future of the band with this crisis ? Do you compose during this quarantine period ?

We’re not a big touring band by any means. We’re lucky if we play a show a month, really – and that’s by choice. We did have some very cool shows in the works, however, as part of a tour I had planned with Afghan-American musician Qais Essar. We don’t really feel any pressure as a band. We play when we want, and we write new music when we feel it. We don’t need to force anything. But I think we all really miss hanging out together - we’re all close friends – and creating music together. I have a bunch of rubab compositions I’d like to play with the guys and see how they feel about it. But for now my focus is more on my debut album with Black Aleph, on my solo material (I’ll have a stand-alone track out soon), and a collaborative project I’m doing with a bunch of Eastern musicians. I mentioned earlier, I’m trying to get better a rubab too. It’s a difficult instrument, and I still have a very long way to go before I feel comfortable.

We wish you the best, and let you conclude this interview. Do you have a last word for our readers ?

Just thank you very much for your interest, it means a lot to us.

Interview made by e-mail in April 2020

Pictures : © Rhiannon Hopley